Oracle separation of PSPACE and PH

Introduction

An important aspect of complexity theory is to try and find separations between different complexity classes. That is, to show that two complexity classes are not equal. One type of separation is a strict containment. It turns out that it is easier to prove containments (for example, give two complexity classes \(A\) and \(\), to show that \(A \subseteq B\), or the opposite, whichever one is true) but to show a strict containment (\(A \subset B\)) is more difficult (\(\mathbf{P}\) vs \(\mathbf{NP}\) being the best example of this). Obviously, a strict containment implies a separation between the two classes, but a containment doesn’t.

So if strict containments are harder to prove, what can we do? One strategy is to try to solve a simpler, related problem: oracle separations. Oracle separations do not imply an actual separation between classes, but one can think of them as a ‘necessary condition’ for it. That is, if a separation indeed exists between two complexity classes, then there definitely exists an oracle separation between them.

The paper I’m going to describe in this post shows an oracle separation between the classes \(\mathbf{PH}\) and \(\mathbf{PSPACE}\), by proving a lower bound on a certain type of boolean circuits, which was a completely original idea at that time. Since then, others have used the idea to show many other interesting results too.

Main result

The main result which is going to be discussed here is that if the \(\mathbf{AC^0}\) circuit (polynomial sized boolean circuits with constant depth, unbounded fan-in) which computes the parity function has size \(\Omega(n^{log^k(n)})\), then there exists an oracle \(\mathbf{O}\) relative to which \(\mathbf{PH^O} \subset \mathbf{PSPACE^O}\). The paper also goes on to show that the parity function indeed requires a \(\Omega(n^{log^k(n)})\) sized circuit to compute, but the proof shown in this paper is relatively complicated. I will probably do another post discussing an alternative proof, which uses Hastad’s Switching Lemma.

Complexity theory: a primer

As the name suggests, complexity theory is about the study of ‘complexity’ of problems. Problems like sorting, shortest path, travelling salesman, or SAT. So how do we define how ‘complex’ a problem is? We need a quantifiable measure, in order to compare it with other problems. One measure is the time taken to correctly compute the solution, given some input. But think about the variables involved here. Surely an algorithm which brute forces its way to the solution, when executed on a speedy brand new processor will execute in less time than a super efficient algorithm running on some 90s era Pentium chip? And what about the language in which we have written the algorithm in? And the compiler used? Would forgetting to specify the -O3 flag during compilation somehow increase the complexity of the program, because it takes more time to execute?

To ‘normalize’ away all these differences, we consider the number of steps taken by the ‘fastest, correct’ algorithm to be the time complexity of the problem. The number of steps required would be a function of the input size, which is usually some natural number, denoted by \(n\). One way of looking at the input size is the number of bits required to completely specify the input for the problem.

Also, intuitively one can deduce the fact that the number of steps required will increase as the input size increases. Which means we can represent the time complexity of problems using monotonically increasing functions.

Complexity theory is more generally concerned with grouping problems of similar complexities together, so that it is easier to characterize them, and compare them with other problems. These groups are what we call complexity classes. One such class, referred to as \(\mathbf{P}\), includes all such problems having time complexity which look like \(n^2\), or \(n^3\), or \(n^4\)… multiplied by a fixed constant. Generally, this fixed constant is the normalization part, and is generally ignored while talking about a problem’s complexity. Another class, known as \(\mathbf{NP}\), is the class of efficiently ‘verifiable’ problems.

For a better understanding of the \(\mathbf{P}\) and \(\mathbf{NP}\) classes, take a look at these lecture notes which cover them, and provide their formal definitions alongside.

Note: One point which the notes don’t mention is that for every string in a language which belongs to \(\mathbf{NP}\), the corresponding certificate is of size polynomial in the string’s length.

coNP

A language’s (say, \(L\)) complement (denoted by \(\overline{L}\)) is the set of all strings which don’t belong to \(L\). Suppose \(L\) is the set of all graphs (or more precisely, the binary representation of such graphs) which have a vertex cover of size at most \(k\). Then \(\overline{L}\) consists of all strings other than those present in \(L\). It will mostly contain binary strings which do not have a valid interpretation as a graph, and among the valid strings, the corresponding graphs will have vertex covers of size more than \(k\).

We say that \(\overline{L}\) belongs to \(\mathbf{coNP}\) if \(L\) belongs to \(\mathbf{NP}\). The most famous example of a language in \(\mathbf{coNP}\) is \(\overline{SAT}\), which consists of all boolean formulae not having even a single satisfying assignment ((\(x_1 \wedge \overline{x_1})\) being an example). Languages belonging to \(\mathbf{coNP}\) don’t have a short certificate (that we know of) that provides a ‘proof of membership’, as in the case of \(\mathbf{NP}\). The formal definition of \(\mathbf{coNP}\) is as follows:

\[x \in L \iff \forall u \text{ } M(x, u) = 1\]Where \(L\) is a language belonging to \(\mathbf{coNP}\), and \(u\) is a variable meant to represent all possible certificates.

PSPACE

This complexity class encapsulates the problems which are solvable by a machine with a polynomial amount of space. There’s no restriction on the time taken to solve the problem, as long as the number of steps taken is finite. It is easy to see how this class encapsulates \(\mathbf{NP}\): simulate a verifier for the problem, cycle through all possible certificates (its length at most polynomial in the input size, so given an input of size \(n\), there exist at most \(2^{p(n)}\) certificates, where \(p\) is some univariate polynomial), and in each cycle, feed the certificate and the input to the verfier. If the verifier accepts for a particular certificate, then accept. Else, if it cycles through all possible certificates and doesn’t accept on any of them, reject.

Polynomial Hierarchy (PH)

This class, often denoted by \(\mathbf{PH}\), encompasses those problems which the classes \(\mathbf{NP}\) and \(\mathbf{coNP}\) are unable to characterize. For instance, consider the \(MAX-INDSET\) problem. Given a graph, an independent set is a subset of vertices such that no two vertices in the subset are adjacent to each other. The \(MAX-INDSET\) problem is concerned with finding the largest independent set for a given graph.

Now, consider the related decision problem. Note that the input has two parts: a description of graph G, and an integer k:

\[INDSET = \{ \langle G, k \rangle: \text{G has an independent set of size at least k}\}\]There exists a short certificate for every valid solution to this problem, namely, the independent set itself. Verifying it is a simple matter of checking that it is of size at least \(k\), and that it forms an independent set, both of which can be done in polynomial time. Therefore this problem lies in \(\mathbf{NP}\).

We can go even further and devise a modification of this problem:

\[\text{EXACT-INDSET} = \{ \langle G, k \rangle: \text{The largest independent set (LIS) of G has size exactly k}\}\]It is not clear whether the definitions of \(\mathbf{NP}\) or \(\mathbf{coNP}\) are enough to characterize this problem. We can find another way to formulate the same problem, though:

\(\text{EXACT-INDSET} = \{ \langle G, k \rangle:\) There exists an independent set of size k, and every subset which is of size more than k is not an independent set \(\}\)

More formally, this can be written as:

\[\text{EXACT-INDSET} = \{ x := \langle G, k \rangle: \exists u\text{ } \forall v \text{ s.t. } M(x, u, v) = 1 \}\]Where \(u\) represents the independent set of size \(k\), and \(v\) denotes a subset of vertices of size more than \(k\), and \(M\) is a function denoting a polynomial time Turing machine computation (it’s ok if you don’t know what a Turing Machine is, just think of it as a formal definition of an ordinary computer system).

Now, we must ensure that \(M\), given an input \(x\), along with \(u\) and \(v\) as defined, carries out a computation which captures the essence of the problem. This can be done if we configure \(M\) to compute the following things (note that all these operations can be done in polynomial time. This is important, the fact that M is a polynomial time machine: it’s where the complexity class derives its name from!) :

- Ensure that \(u\) is of size \(k\), and that it is indeed an independent set.

- Similarly, ensure that \(v\) is of size more than \(k\), and that it is not an independent set.

- If for a given \(x\), \(u\), \(v\), the two conditions mentioned above are satisfied, then output \(1\). Else, output zero.

We can create another program which given input \(x\), and descriptions of the variables \(u\), \(v\), and a description of the behaviour of \(M\), will cycle through all possible combinations of \(u\) and \(v\), running the machine \(M\) for each combination. and if it finds a particular \(u\) such that when combined with all possible \(v\), \(M\) outputs 1 every single time, then we have found our solution.

Else, if the LIS isn’t of exactly of size \(k\), either of two cases are possible. The first case is that the LIS has size strictly lesser than \(k\). In this event, the outer program won’t be able to find a suitable candidate for \(u\) at all, and the inner program will return zero each time. The second case is when the LIS has size strictly greater than \(k\), whereupon we are guaranteed that for some \(v\) corresponding to that LIS, and for some subset of \(v\) of size equal to \(k\), the inner computation will return zero. Thus we have defined a framework which completely characterizes the \(EXACT-INDSET\) problem. (Note that I have used the terms program, computation and machine interchangeably).

It turns out that that this framework is applicable to many problems, and we have a name for it: \(\Sigma_2^p\). The \(\Sigma\) indicates that the first quantifier is existential, the \(2\) indicating that we use two quantifiers, and the \(p\) simply saying that we are only using polynomial time computations (this does not mean that the problem is computable in polynomial time! Observe that we use an exponential number of polynomial time computations to characterize the input).

We can define the class \(\Pi_2^p\) similarly. For any language \(L \in \Pi_2^p\):

\[x \in L \iff \{\forall u \text{ } \exists v \text{ s.t. } M(x, u, v) = 1 \}\]The sizes of variables associated with the quantifiers that we’ve defined up until this point (and will define later) are polynomial in the size of the input.

An example of a problem in \(\Pi_2^p\) is the \(MIN-CNF\) problem: given a 3-CNF boolean formula (each clause having three variables with two \(OR\) operators, the clauses themselves acted upon by \(AND\) operators), find an equivalent boolean formula having fewer clauses.

This problem can be restated as follows: A 3-CNF boolean formula (more precisely, its string representation) lies in \(MIN-CNF\) iff for every 3-CNF boolean formula having more clauses, there exists an assignment of inputs for which the two formulas give different outputs (that is, the two formulas are not equivalent). It is easy to see that \(MIN-CNF \in \Pi_2^p\).

We can now generalize the notion of \(\Pi_2^p\) and define the class \(\Pi_i^p\). For any language \(L \in \Pi_i^p\), the following holds:

\[x \in L \iff \{\forall u_1 \text{ } \exists u_2 \text{ } \forall u_3 \ldots Q_i u_i \text{ s.t. } M(x, u_1, u_2, u_3, \ldots, u_i) = 1 \}\]Where \(Q_i\) is an existential or a universal quantifier depending on whether \(i\) is even or odd. We can define \(\Sigma_i^p\) in a similar manner. Note that the quantifiers are alternating with one another, because if we had two quantifiers of the same type adjacent to one another, it is always possible to combine them.

The complexity classes generated by the generalizations have some very neat relationships among them (they apply to all \(i>0\)):

- \(\Pi_i^p \subseteq \Pi_{i+1}^p\) (similarly for \(\Sigma_{i}^p\))

- \(\Sigma_i^p \subseteq \Pi_{i+1}^p\) (similarly for \(\Pi_{i}^p\))

- \(\Pi_i^p = co\Sigma_i^p\) (uses the fact that negation of an existential quantifier is a universal quantifier, and vice versa).

And finally, after all these definitions, we arrive at the complexity class we’ve all been waiting for!

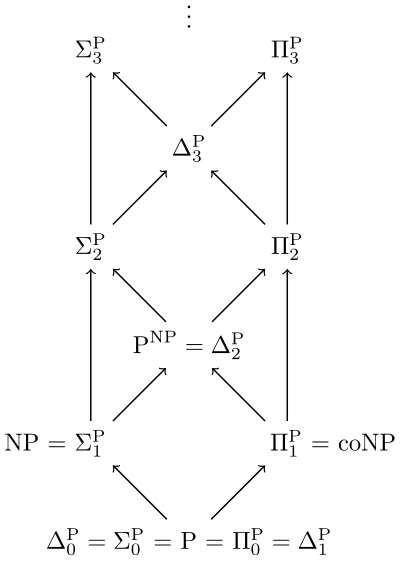

\[\mathbf{PH} = \bigcup_{i} \Sigma_i^p = \bigcup_{i} \Pi_i^p\]Okay, that was a bit anti-climatic. But \(\mathbf{PH}\) is an interesting class to study, as we shall soon see. The classes can be visualized in the form of a ladder. An arrow from a class \(A\) to class \(B\) indicates a containment (that is, \(A \subseteq B\)):

(\(\Delta_i^p\) is just the intersection of \(\Sigma_{i+1}^p\) and \(\Pi_{i+1}^p\), but we don’t need to be concerned with those.)

The most amazing thing about \(\mathbf{PH}\) is that we don’t know whether any of these containments are strict or not (as I mentioned earlier, we are very bad at proving/disproving strict containments, and many believe we haven’t developed the requisite mathematical tools yet).

We believe that all these containments are strict, for if it turns out that even one of the containments holds the other way as well (that is, both classes are one and the same), then the polynomial hierarchy ‘collapses’ to that level.

Put more formally, it means that in the event that \(\Sigma_{i+1}^p = \Sigma_i^p\) holds for some particular \(i\), then it would mean that \(\Sigma_j^p = \Sigma_i^p\) for all \(j>i\) (similarly for \(\Pi_i^p\)). In other words, the polynomial hierarchy collapses to level i. The other case where it would collapse is if \(\Pi_i^p = \Sigma_i^p\) for some \(i\).

It is unnatural that the polynomial hierarchy would collapse, since it definitely seems like we are getting more ‘power’ by adding more quantifiers. This is also one of the reasons why many believe that \(\mathbf{P} \neq \mathbf{NP}\), and that \(\mathbf{NP} \neq \mathbf{coNP}\).

Relationship between PSPACE and PH

One would realize after a moment’s thought that \(\mathbf{PH} \subseteq \mathbf{PSPACE}\), because you only need a polynomial amount of space to simulate the Turing Machine denoted by ‘\(M\)’ in the definitions, and a variable whose value you would toggle if a zero was outputted by one of the computations. Of course, as mentioned earlier, we don’t know whether this containment is strict or not.

Oracles

An Oracle Turing machine is a Turing machine with access to a certain oracle. Oracles are machines which solve the decision problem for some language \(O\) in just a single computational step, no matter how computationally hard \(O\) is (the oracle itself is denoted by \(O\) too). At any point during its computation, a TM can write down a string and ask the oracle, ‘does this string lie in O?’, and get back an answer in the very next step. It can query the oracle as many times as it wants to, on any random string of its choosing.

By the definition, it is obvious that the oracle gives the TM some additional power, and also that the oracle is just a ‘convenience’ which allows us to black box the hardness of computing any particular language, and that it does not have any real world analogues.

A few more definitions before we get to the next section (where I actually start discussing the paper (!)): a language is denoted by \(L^O\) if there is a TM with access to oracle \(O\) which decides \(L\). The complexity class \(\mathbf{P^O}\) is defined as the set of all languages which can be decided by a polynomial time TM with access to oracle \(O\). The analogues to other complexity classes are defined in a similar manner.

As a reminder, the goal of the paper that I’m discussing here is to give some evidence for the belief that \(\mathbf{PH} \subset \mathbf{PSPACE}\), and showing that \(\mathbf{PH^O} \subset \mathbf{PSPACE^O}\), where \(O\) is some valid oracle, is one way of doing so, and this paper gives us such an oracle.

Train of thought

We will first define a certain language which we’ll call \(L^A\) (the TM which decides this language has access to oracle A), and show that it lies in \(\mathbf{PSPACE^A}\). Then we assume that \(L^A \in \mathbf{PH^A}\), which means that there’s a level \(i\) in the polynomial hierarchy in which \(L^A\) is contained (\(L^A \in \Sigma_i^{p, A}\) for some \(i\)). Next, it is shown that given the previous assumption (\(L^A \in \mathbf{PH^A}\)), there must exist a \(O(polylog(n))\) circuit computing the parity function.

But this is where it gets interesting! The second part of the paper (which I won’t be discussing) proves that a \(O(polylog(n))\) sized parity-computing circuit doesn’t exist, which means \(L^A\) is not in \(\Sigma_i^{p, A}\) for any \(i\), which means \(L^A \not\in \mathbf{PH^A}\). Thus, we will have proved that \(\mathbf{PH^A} \subset \mathbf{PSPACE^A}\).

First Step: Defining \(L^A\)

\[L^A = \{1^n | \text{Number of n-length strings in A is odd}\}\]Assume \(A\) to be some language. The language \(L^A\) is defined relative to the strings present in \(A\). It only happens to contain at most one string of any given length, and if it does happen to contain a certain string of length \(n\), then it will be made up of all ones. What is the condition under which \(L^A\) will contain an \(n\)-length, all-ones string? Only when the language A has an odd number of \(n\)-length strings in it.

Right away, by looking at the definition of \(L^A\), it seems obvious that it has some connection to the parity function. In fact, it has been defined such that it has this connection, which we’ll exploit later. What’s also obvious is that this language exists in \(\mathbf{PSPACE^A}\). Consider the following procedure: upon being given a \(n\)-length string, proceed further only if it is an all-ones string (reject if not). Then, simply query oracle A all possible \(2^n\) strings of length \(n\), and accept only if the number is odd. All this can easily be done by a TM having space polynomial in the size of input.

Second Step: Showing existence of an \(O(polylog(n))\) sized parity-computing circuit

We’ll be showing this under the assumption that \(L^A\) is in \(\mathbf{PH^A}\). As stated above, this implies that \(L^A \in \Sigma_i^{p, A}\). This means that:

\[x \in L^A \iff \{ \exists y_1 \forall y_2 \ldots Q_iy_i s.t. M^A(y_1, y_2, \ldots , y_i, x) = 1\}\]where \(M^A\) is a TM with the modification that is has access to oracle A. Next, we claim that:

\[M^A(y_1, y_2, ... y_i, x) = \exists r \forall s \overline{M^A}(y_1, y_2, ... y_i, r, s, x)\]Where \(\overline{M^A}\) is similar to \(M^A\), but with two modifications: one, it can only make one oracle query (\(M^A\), of course, can make a polynomial number of queries to the oracle), and two, it has two additional inputs. Note the trade off here: \(\overline{M^A}\) is ‘equal’ in power to \(M^A\), even though the number of queries which can be asked has been restricted. This is because we have now ‘ascended’ two levels higher in the polynomial hierarchy. But why should the trade-off be true?

To see this, consider the machine \(M^O\), whose computations are identical in nature to \(M^A\), except that we can swap in any oracle we want. Now fix an input \(x\), along with some valid combination of \(y_1, ... y_i\), and then think of the computation of a certain TM \(M^O\) in the following manner: Each time the TM enters into a state where it queries the oracle, it can end up in one of two states, depending upon the oracle (or, more precisely, its answer to that query). Therefore, if we decide that we want to ‘track’ all possible ‘computational paths’ down which the TM might go, we will notice that we get a binary tree. Each path will correspond to a different oracle. Furthermore, as long as the inputs are fixed, the computational path taken by the TM is wholly dependent on the responses of the oracle (think about why this is true).

Now, suppose we fix an input \(x\) which is in \(L^A\), and also some combination of \(y_1, ..., y_i\), which automatically fixes a corresponding computation graph for \(M^O\). Recalling the definition of \(\Sigma_i^{p, A}\), we can see that \(M^A\) must output \(1\) no matter what \(y_1, ..., y_i\) we have chosen. Therefore, since we now know that there exists at least one oracle for which \(M^O\) outputs 1, we can be sure that there exists a branch in the graph whose query-response pairs at each ‘branching’ matches the response of oracle A, when it is queried that particular query. This branch is the exact branch taken by \(M^A\). Additionally, the state at the end of the path will be an accepting one.

Now, it is easier to see how the two machines are equivalent. Take ‘\(r\)’ to be an accepting path, which is characterized by a sequence of query-response pairs, and allow ‘\(s\)’ to range over all possible queries. Therefore, given a particular \(r\) and \(s\), what \(\overline{M^A}\) will do is it will simulate \(M^A\), and each time it reaches a point where it has to query the oracle, it just uses the corresponding response from the sequence represented by ‘\(r\)’. In case the query matches the query represented by ‘\(s\)’, \(\overline{M^A}\) will actually query the oracle and indeed verify that the query-response pair is indeed right. If the response does not match the one given by the oracle, then the machine rejects (this is the only case where \(\overline{M^A}\) will reject, and if \(x\) does not belong to \(L^A\), there will be an incorrect query response pair in ‘\(r\)’, and a corresponding query ‘\(s\)’, so \(\overline{M^A}\) will reject when it comes to that ‘\(s\)’). Stepping back, it is easy to see that if \(x\) actually belongs to \(L^A\), then \(\overline{M^A}\) will, by iterating through all possible queries, chance upon each query specified in the sequence represented by ‘\(r\)’, and will verify the whole sequence correctly.

A thing to note here is that \(\exists r \text{ } \forall s \overline{M^A}(y_1, y_2, ... y_i, r, s, x)\) is equivalent to \(\forall s \text{ } \exists r \overline{M^A}(y_1, y_2, ... y_i, r, s, x)\) since the variables ‘\(r\)’ and ‘\(s\)’ are unrelated to each other. Also note that this switching is not possible in every case. For example, the \(MIN-CNF\) problem described above, lies in \(\Pi_2^p\), but does not lie in \(\Sigma_2^p\) (at least, we don’t know that it does), because switching the variables is not possible in this case.

We are in a position to go a step further and claim that \(L^A\) in fact lies in \(\Sigma_{i+1}^{p,A}\) (with regards to the \(\overline{M^A}\) machine, that is. It is trivially in \(\Sigma_{i+1}^{p,A}\) for the \(M^A\) machine). Depending upon whether \(Q_i\) is \(\forall\) or \(\exists\), we replace \(M^A(...)\) with the equivalent \(\forall s \text{ } \exists r \text{ } \overline{M^A}(...)\) or \(\exists r \text{ } \forall s \text{ } \overline{M^A}(...)\) version, and then the two consecutive universal (or existential) quantifiers can be merged into one.

We are now almost ready to construct the parity-computing circuit, we just need a couple of things in order.

First, think of the following NP statement:

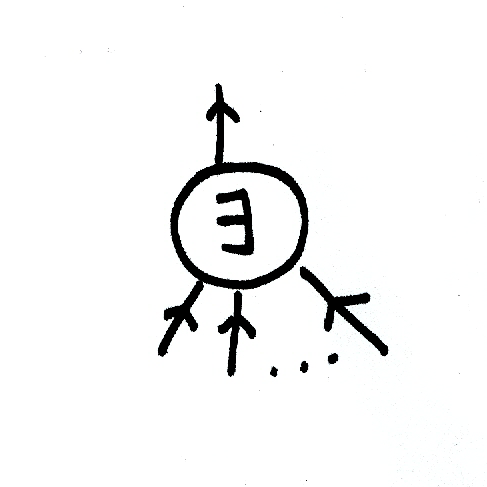

\[x \in L \iff \exists y \text{ } M(x, y) = 1\]This can be thought of as (I hope you will forgive me for the bad drawings that follow!):

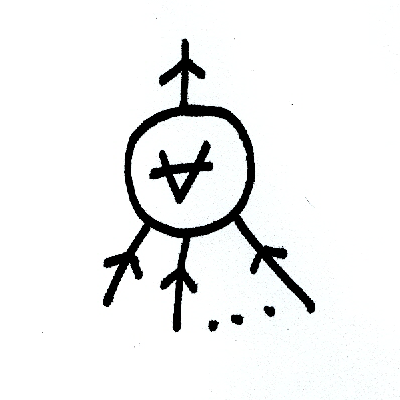

where the \(\exists\) node acts like the OR gate, outputting \(1\) only when at least one of \(M(x, y_i)\) evaluates to \(1\). You can think of a similar construction for coNP:

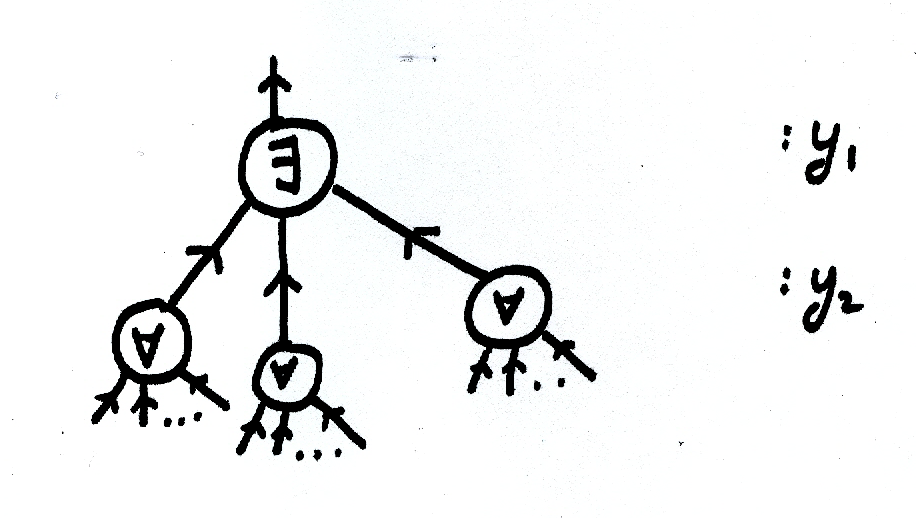

A construction for \(\Sigma_2^p\) will look like:

Now, extending this concept a bit further, we can think of any \(\Sigma_i^p\) computation as a tree of nodes, with the levels alternating between \(\exists\) and \(\forall\). Each of the leaves would then correspond to a computation, with the inputs as some particular combination of \(y_1,...y_n\). It is quite easy to see that the construction outputs \(1\) if and only if \(\exists y_1... M^A(y_1, ..)\) evaluates to true.

Now, consider the \(\Sigma_{i+1}^p\) computation where we use \(\overline{M^A}(y_1, y_2, ..., y_{i+1}, x)\). Each particular computation’s output, it turns out, can be associated with the response of the query it makes to the oracle during the course of its computation (Remember, \(\overline{M^A}\) only makes a single query).

The query made to the oracle is one of \(\approx 2^n\) possible queries, which can be denoted by \(q_1, q_2, ..., q_{2^n}\), and their corresponding responses by \(r_1, r_2, ..., r_{2^n}\). Suppose during computing \(\overline{M^A}(y_1, y_2, ..., y_{i+1}, x)\), the machine queries the oracle for \(q_j\) and receives \(r_j\) as response. Since the output of \(\overline{M^A}(y_1, y_2, ..., y_{i+1}, x)\) and the quantity \(r_j\) are both boolean variables, either one of \(\overline{M^A}(y_1, y_2, ..., y_{i+1}, x) = r_j\) or \(\overline{M^A}(y_1, y_2, ..., y_{i+1}, x) = \overline{r_j}\) holds true.

It follows that we can label the leaves of the computation tree with \(r_j\) (or \(\overline{r_j}\)) now (note that this does not mean that the construction only has \(\approx 2^n\) leaves. In fact, the number of leaves far exceeds that number). Now, by having an understanding of how we can construct a ‘\(\forall\exists\) circuit’, and knowing that the particular construction we created outputs \(1\) only when the number of \(n\)-length strings in A is odd, and by modifying the circuit by replacing every \(\forall\) node with an \(AND\) gate, every \(\exists\) node with an \(OR\) gate, we get a circuit which computes the parity of the \(2^n\) bits represented by the bits (\(r_j\) or \(\overline{r_j}\)) at the leaves of the circuit.

Going the other way, we can look at it as follows: Given \(2^n\) input bits (if the number of bits in the input isn’t a power of \(2\), pad it with zeroes. The parity value won’t change!), label them as \(r_1, r_2, ..., r_{2^n}\). Now arrange all the \(2^n\) \(n\)-length strings in lexicographical order, and add the \(i\)th string to a set if \(r_i = 1\). This set is now the language \(A\). Therefore, \(L^A\) will contain \(1^n\) only if parity of the input bits is equal to 1, and everything else follows. It might be the most convoluted way ever to calculate parity, but it works.

One other useful thing of note is that during the computation of \(M^A\), where \(M^A\) has to decide whether or not a given \(x\) is present in \(L^A\) or not, it will query the oracle of every possible \(n\)-length string, \(n\) being the length of \(x\). How do we know this? Because of how \(L^A\) is defined, the inclusion of string \(x\) in it depends upon the fact that it is completely made up of ones, and that an odd number of \(n\)-length strings are present in A. Therefore, since \(M^A\) does not have any ‘built-in’ knowledge of language A, and because of the fact that it can only know anything all about A is by querying the oracle, and because if the machine misses out on querying even a single \(n\)-length string it may give the wrong answer, it has no choice but to query every possible string. For those in the know, this is a consequence of the fact that the communication complexity of the parity function is \(n\).

The only thing left to do is to derive the size of the circuit. Since every variable \(y_i\) is of length at most polynomial in \(n\), assume it is of length at most \(n^k\), for some \(k\). Then, it follows that every internal node must have \(2^{n^k}\) children, one for each possible value of \(y_i\). Using this, the size of the circuit comes out to be \(O(2^{n(log^k(2^n))})\). Since we are using a \(2^n\) sized string as input, if we replace \(2^n\) by \(n'\), we have an \(O(n'^{(log^k(n'))})\) sized circuit for computing parity.

This proof not just proves the existence of a \(O(n^{log^k(n)})\) sized circuit for computing the parity of \(n\) bits, but gives details for constructing one as well. Of course, this is under the assumption that \(L^A\) lies in \(\mathbf{PH^A}\).

The second section of the paper essentially proves the contrapositive of the above statement. It shows that a \(O(n^{log^k(n)})\) sized circuit for computing parity of \(n\) bits does not exist, thus \(L^A \not\in \mathbf{PH^A}\), proving the existence of an oracle relative to which \(\mathbf{PH} \subset \mathbf{PSPACE}\).

There are a few additional implications about the second result in the paper, like multiplication and the majority function don’t lie in \(AC^0\) as well, but the most significant implication, by far, is the one discussed above.

Conclusion

Oracle separations are an interesting way to glean evidence about things which we have no idea how tackle, given the available tools. A much more recent oracle separation was shown by Ran Raz and Avishay Tal in 2018, between \(BQP\) and \(PH\) (it showed \(BQP^A \not\subset PH^A\), which is surprising enough in its own right).