Mergers from Kakeya Sets

Introduction

Consider the following problem: given \(k\) probability distributions, with the guarantee that at least one of them is the uniform distribution, the task is to come up with a procedure that ‘merges’ these distributions and obtains a distribution which is uniform. We do not know which of the \(k\) distributions is uniform, and to make things interesting, the other distributions can be correlated among themselves, and also with the uniform distribution. Moreover, this ‘merging’ procedure is required to be ‘blind’ in a certain sense, meaning that we are not providing it with any information regarding the probabilities associated with the inputs.

What does the last sentence mean, really? It becomes clearer once we formalize the above paragraph. Taking our sample space to be \(\{0, 1\}^n\), we require the function (we’ll call it a merger henceforth) to be of the following form: \[ f: \{0, 1\}^{n \times k} \rightarrow \{0, 1\}^n, \] and also satisfy the requirement that the function outputs every string in \(\{0, 1\}^n\) with equal probability, given that the inputs provided to the function are sourced from the distributions described in the previous paragraph. More formally, for every \(y \in \{0, 1\}^n\), the sum of the probabilities of those inputs in the pre-image of \(y\) has to add up to \(2^{-n}\). In mathematical notation: \[ \forall y \in \{0, 1\}^n \sum_{x \in f^{-1}(y)} Pr[X=x] = 2^{-n} \] Hopefully, the function signature should makes the last statement in the first paragraph clear. The function will be given a bit string of length \(n \times k\), and has to output a bit string of length \(n\). It does not have any information about the probability with which the provided input is being sampled with. This might seem like a daunting task at first sight, but it has a surprisingly elegant solution, which I will describe in this blog post.

Now to be completely honest, I lied in a few places in the definition above. Firstly, to ask for the output distribution to be strictly uniform on \(n\) bits is very restrictive, and we can relax this condition in two ways: first, instead of asking for the output distribution to be uniform, we can ask for it be a high min-entropy distribution. A distribution on \(\{0, 1\}^n\) has min-entropy \(t\) for some \(t \leq n\) if every string is sampled with probability at most \(1/2^t\). It is easy to see that the uniform distribution has min-entropy equal to \(n\), and also that intuitively, greater the min-entropy of a distribution, greater the amount of ‘randomness’ contained within it. Second, we can ask for the output distribution to be close in statistical distance to some high min-entropy distribution, instead of asking for it to be exactly equal to one. This relaxation is OK, because every Boolean function still ‘behaves’ similarly on a statistically-close-to-uniform distribution, to as it would on a uniform distribution.

Lastly, we need a small amount of additional randomness for the function to work, and it is easy to see that any deterministic function cannot be a good merger. To see this, consider just two sources, and the output to be just one bit. Even in this easy special case, any deterministic function of the form \[ f: {0, 1}^n \times \{0, 1\}^n \rightarrow \{0, 1\} \] will not work. That is, for any given \(f\), there exist distributions \(X_1, X_2\) on \(\{0, 1\}^n\), with one of them being uniform, such that the output of \(f\) will be far from uniform. It is left as an exercise to the reader to work out for themselves why this is true!

Kakeya Sets

In the world of finite fields, a Kakeya set is a subset of \(\F_q^n\) containing a line in every direction, up to translation. Precisely, a susbet \(K \subseteq \F_q^n\) is a Kakeya set if for every element \(\F_q^n\), there exists an element \(y \in \F_q^n\) such that \[ \forall a \in \F_q, y + ax \in K. \]

An interesting question to ask is: what is the smallest possible size of a Kakeya set? A lower bound of \(q^{n/2}\) is easy to see: every Kakeya set has the useful property that the set \[ S := \{x - y : x, y \in K\} \] fills up the entire space of \(\F_q^n\). This is because following the definition of a Kakeya set, for any vector \(z \in \F_q^n\), there exists a \(y \in \F_q^n\) such that both \(y \in K\), and \(y + z \in K\). Therefore, we get \(z\) by subtracting \(y\) from \(y+z\). Now, one can see that if \(S\) has to contain \(q^n\) vectors, then \(S\) has to satisfy: \[ q^n \leq |S|, \] and we use the fact that \[ |S| \leq |K|^2 \] to get what we want. The last inequality is true because there are \(|K|^2\) ways to choose a tuple \((x, y) \in K^2\).

But what do Kakeya sets have to do with mergers? Dvir and Wigderson in this paper come up with a surprisingly simple construction for a merger, whose analysis relies on analyzing ‘approximate’ Kakeya sets. This merger construction allows them to plug it into another construction of a much more powerful pseudorandom object called an extractor, and results in an extractor with optimal parameters. We won’t talk about extractors here, but this chapter from Vadhan’s book is a great introduction to the topic.

The merger construction works entirely over the field \(\F_q\), for an appropriately chosen \(q\). We will represent the binary strings from \(\{0, 1\}^n\) as vectors from \(\F_q^r\) (where \(r\) will be a divisor of \(n\)) and work with them, and converting back to the binary representation once we have the output. ‘Lifting’ up the binary strings to a higher alphabet allows us to use the properties of the ‘approximate’ Kakeya sets in order to analyze the behaviour of the merger.

Merger Construction

I won’t list out all the parameters here, or the reasoning behind their values, since the original paper already has them, and moreover, there’s a lot of them. Instead, I will only mention the essential ones, and try to give some intuition on how the merger behaves. We take \(q\) roughly to be equal to \(nk\), recalling that \(k\) is the number of sources. We will work with the field \(\F := \F_q\). For simplicity, we will also take \(n\) to be a multiple of \(\log_2 q\), because then we can represent any \(n\)-bit binary string as a vector from \(\F^r\), where \(r:= n/\log_2 q\). From here on, we can think of the merger \(M\) as a function of the form \(M: (\F^r)^k \rightarrow \F^r\) (compare this to \(f\)’s signature in the introduction). Lastly, we will keep with the convention of using capital letters to denote random variables, and small letters to denote the values they take.

\(M\) is defined as: \[ M(X_1, \ldots, X_k, U) := c_1(U)\cdot X_1 + \ldots + c_k(U)\cdot X_k \] where each \(X_i\) is some distribution on \(\F^r\) (that is, after lifting it from a distribution on \(\{0, 1\}^n\)), \(U\) is a random variable uniformly distributed on \(\F\) which represents the additional randomness that the merger requires, and each \(c_i(.)\) is a univariate polynomial from the ring \(\F[u]\). These polynomials are an indicator function of sorts: we shall first fix elements \(\gamma_1, \ldots, \gamma_k\) from \(\F\), and then construct the polynomials such that \(c_i(u)\) will be equal to \(1\) when \(u=\gamma_i\), will be equal to \(0\) when \(u=\gamma_j\) for \(j \neq i\), and will take on some value from \(\F\) when the input is not any of \(\gamma_1, \ldots, \gamma_k\).

Aside from the above description, the only other fact that we will use about the polynomials \(c_1, \ldots, c_k\) is that they all have degree at most \(k-1\); but if you’re still curious about them, here’s how they look: \[ c_i(u) := \frac{\prod_{j \neq i} (\gamma_j - u)}{\prod_{j \neq i}(\gamma_j - \gamma_i)} \]

High Level Idea

The claim is that the merger’s output distribution (which is a distribution over \(\F^r\)) is close to some high min-entropy distribution. For the sake of contradiction, we will assume that it is far from every high-min entropy distribution, which implies the existence of a small set \(T \subset \F^r\) on which a large probability mass is placed by the merger’s output distribution. The high level idea is to show that this set is some approximate form of a Kakeya set in \(\F^r\), and therefore it cannot be too small, thus arriving at the contradiction.

To show that this set \(T\) cannot exist, we will use the polynomial method, along the lines of Dvir’s proof for the lower bound on the size of a Kakeya set in \(\F^n\). This will involve

- proving that existence of \(T\) implies the existence of a non-zero polynomial \(g: \F^r \rightarrow \F\) of low degree which completely vanishes on \(T\) (meaning that for every \(t \in T, g(t)=0\)),

- constructing a set \(G \subseteq \F^r\) whose size is much larger than the size of \(T\),

- showing that \(g\) vanishing on \(T\) implies that \(g\) must necessarily vanish on \(G\) as well.

- This will imply that either \(g\) is the zero polynomial, or has high degree, both of which are not true. Therefore, this implies such a \(g\) does not exist, which in turn implies that such a \(T\) does not exist.

In the next section, we will show why the merger’s output distribution being far away from every high-min entropy distribution implies that such a small set \(T\) must exist, and in the subsequent sections, we will go over each of the steps in detail.

Existence of small set \(T\)

WLOG, we will assume that \(X_1\) is the uniform distribution. The claim is that for every set of distributions \(X_1, \ldots, X_k\) where \(X_1\) is uniform on \(\F^r\), the merger’s output distribution is \(\epsilon\)-close to some distribution having min-entropy \((1-\alpha)r\), where \(\alpha\) is a very small constant. For contradiction, assume that this merger promise does not hold, i.e, there is some set of distributions \(X_1, \ldots, X_k\) with \(X_1\) uniform, and yet the merger’s output distribution is at least \(\epsilon\)-far from every distribution of min-entropy \((1-\alpha)r\). This implies that there is a small set \(T \subset \F^r\) of size at most \(q^{(1-\alpha)r}\) such that the merger’s output places a substantial probability mass on it. Formally: \[ \Pr_{X_1, \ldots, X_k, U}[M(X_1, \ldots, X_k, U) \in T] \geq \epsilon. \]

The existence of such a \(T\) can be shown via a proof of contradiction as well. Therefore, assume that for every set \(S \subset \F^r\) where \(|S| \leq q^{(1-\alpha)r}\), the following holds: \[ \Pr_{X_1, \ldots, X_k, U}[M(X_1, \ldots, X_k, U) \in S] < \epsilon. \] Now, consider all elements that are ‘witnesses’ to the fact that \(M(X_1, \ldots, X_k, U)\) does not have min-entropy \((1-\alpha)r\), that is, all \(x \in \F^r\) such that \(\Pr_{X_1, \ldots, X_k, U}[M(X_1, \ldots, X_k, U) = x] > q^{(1-\alpha)r}\). There can only be at most \(q^{(1-\alpha)r}\) such elements, otherwise their combined probabilities will exceed one. Now, because of our assumption, this set of elements has at most \(\epsilon\) probability mass on it. If we move away all of the mass to elements which have very low mass, then the new distribution that we have created has min-entropy at least \((1-\alpha)r\) (because we have ‘eliminated’ all of the ‘witnesses’), and we only moved \(\epsilon\) mass in doing so, therefore the new distribution is \(\epsilon\)-close to the new distribution. This contradicts the fact that the original distribution is \(\epsilon\)-far from every distribution having min-entropy at least \((1-\alpha)r\).

Existence of polynomial \(g\)

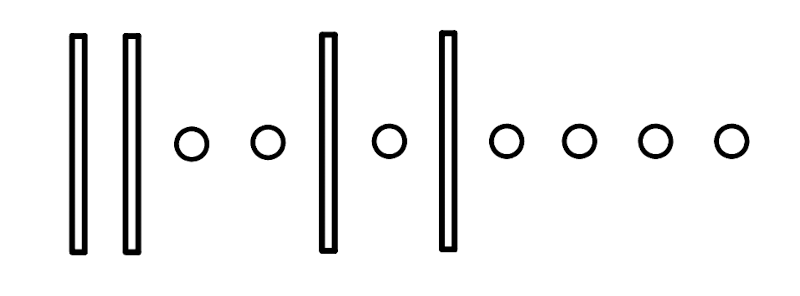

In this section, we show the existence of a polynomial \(g: \F^r \rightarrow \F\) of total degree at most \(d := q^{1-\alpha}\), which completely vanishes on \(T\). Firstly, note that the number of \(r\)-variate monomials having degree at most \(d\) is equal to: \[ {r+d \choose r}. \] One way to see this is by placing \(d\) marbles in a row, and counting the number of ways \(r\) sticks can be placed in between the marbles, or at either end. Here is one possible arrangement for \(d=7, r=4\):

Each such arrangement corresponds to a monomial whose total degree is less than \(d\). The number of marbles to the left of the \(i\)th stick, and to the right of the \(i-1\)th stick is equal to the degree of variable \(x_i\). Therefore, the above arrangement corresponds to the monomial \(x_1^0x_2^0x_3^2x_4^1 = x_3^2x_4\).

Finally, the value for \(r\) has been cleverly chosen such that \[ {r+d \choose r} \geq |T| \] is true. This implies that there is a non-zero polynomial \(g: \F^r \rightarrow \F\) having total degree at most \(d\) that vanishes on \(T\). This is easily seen by solving for \(Ax=0\), where \(A\) is a matrix of dimension \(|T| \times {r+d \choose r}\), with each column corresponding to a monomial, and the entries being the evaluations of the monomial on points from \(T\). This is a matrix having full rank, and therefore one can find an \(x\) satisfying \(Ax=0\). The entries of \(x\) will determine the coefficients of \(g\), the polynomial whose existence we wanted to show.

Constructing the (much) larger vanishing set \(G\)

Where do we even begin? We don’t know anything about the structure of the polynomial \(g\). All we know is that it is a polynomial of low-degree which vanishes on \(T\). At first glance, it might seem like there isn’t much to work with, if we want to build a larger vanishing set for \(g\), but the unique structure of \(T\) will come to our rescue.

We will consider all elements \(x_1 \in F^r\) such that if we condition on the event \(X_1 = x_1\), then the merger’s output will fall into \(T\) with high probability. That is, the following set \(G\): \[ G := \{ x_1 \in \F^r \mid \Pr_{X_1, \ldots, X_k, U}[M(X_1, \ldots, X_k, U) \in T \mid X_1 = x_1] \geq \epsilon/2 \}. \] We will show that for every \(x_1 \in G\), \(g(x_1)=0\).

At this point, the observant reader should be thinking: how is it that an element that with high probability over the other random variables takes \(M\)’s output to \(T\), also makes \(g\) vanish when we give that element as an input to \(g\)? This question will be answered duly, but first we must state that the size of \(G\) is large: \[ |G| \geq \frac{\epsilon}{2}q^r. \] This follows from a simple averaging argument, but I won’t go into it here. Lastly, one interesting fact to note is that \(T\) was defined as a subset of the range of \(M\), while \(G\) was defined as a subset of the space corresponding to the first input of \(M\).

g vanishing on \(T \implies g\) vanishing on \(G\)

We mentioned in the previous section that \(T\) has some unique structure, which is somewhat like an approximate Kakeya set. We make this notion precise in this section.

Firstly, recall that by the definition of \(G\), for every \(x_1 \in G\), we have \[ \Pr_{X_1, \ldots, X_k, U}[M(X_1, \ldots, X_k, U) \in T \mid X_1 = x_1] \geq \epsilon/2. \] This implies that there exist values \(x_2, \ldots, x_k \in \F^r\) that we can assign to the other random variables \(X_2, \ldots, X_k\) such that we get: \begin{equation} \Pr_{X_1, \ldots, X_k, U}[M(X_1, \ldots, X_k, U) \in T \mid X_1 = x_1, X_2=x_2,\ldots,X_k=x_k] \geq \epsilon/2. \end{equation} At this point, the only remaining randomness is coming from \(U\), which was the random variable used as input to the polynomials \(c_i(.)\), in the construction of the merger.

This means that after we have fixed an \(x_1 \in G\) and also fixed the corresponding \(x_2, \ldots, x_k\) as specified above, the merger function is of the form \(M_{x_1, \ldots, x_k}: \F \rightarrow \F^r\), where the only variable left is the input to the polynomials \(c_i(.)\). The subscript of \(x_1, \ldots, x_k\) for \(M\) is used to denote that those inputs to \(M\) have already been fixed. Now, observe from the above inequality that \(T\) contains an \(\epsilon/2\) fraction of points from the image of the function \(M_{x_1, \ldots, x_k}\).

We are now in a position to state how \(T\) is like an approximate Kakeya set: because \(G\) contains an \(\epsilon/2\) fraction of points in \(\F^r\), we can carry out the above procedure for every \(x_1 \in G\), and create a corresponding function \(M_{x_1, \ldots, x_k}\) such that an \(\epsilon/2\) fraction of the points from the image of the function fall into \(T\). Compare this to a natural definition of an approximate Kakeya set: a set containing a large fraction of points for a large fraction of directions in the vector space. Our set \(T\) is a generalized version of this, containing a large fraction of points for a large fraction of functions whose image is a subset of the vector space.

We turn to the main task of this section: to prove that \(g(x_1)=0\) for every \(x_1 \in G\). Given any \(x_1 \in G\), we first construct \(M_{x_1, \ldots, x_k}(.)\), and then define \(h(u) := g(M_{x_1, \ldots, x_k}(u))\), as detailed above. Recall that by its definition, \(h\) has the form \(h: \F \rightarrow \F^r\). The definition of \(h\) might seem a bit strange: we want to prove the \(g(x_1)=0\), where \(x_1\) is the first input to the merger, but we have defined \(h\) by passing the output of the merger to \(g\). How is this going to be of any help? The trick is noticing that \(h(\gamma_1) = g(x_1)\), by how the merger was defined. We will now prove that \(h(\gamma_1)=0\), which will give us what we require. In fact, we will prove something much stronger: \(h(u)\) is identically zero for all inputs \(u\)!

We have already done the bulk of the work to show this result, actually. The last inequality written above states that for an \(\epsilon/2\) fraction of \(u \in \F\), \(h(u)=g(M(x_1, \ldots, x_k, u))=0\). This follows because \(g\) is zero on every point in \(T\). Therefore, we get that \(h\) is zero on an \(\epsilon/2\) fraction of its inputs. But from the definition of \(h\) we can see that it is just a degree \(k-1\) polynomial in \(\F\). Because we have chosen \(q\) to be equal to \(nk\), the Schwartz-Zippel lemma says that the only way \(h\) can \(\epsilon/2\cdot q\) zeroes is if it was the zero polynomial, or if it had degree \(q\). We know that it has degree strictly less than \(q\), and therefore it has to be the zero polynomial, and hence \(h(u)\) is identically zero for all inputs \(u\).

Conclusion

The result proved in the above section in turn implies that again, by the Schwartz-Zippel lemma, because \(g\) is zero on \(\epsilon/2\cdot q^r\) inputs, it must either be the zero polynomial, or have degree \(q\). But this contradicts the fact that \(g\) was a nonzero polynomial of degree \(q^{1-\alpha} < q\) to begin with, and therefore, such a \(g\) could not have existed. Because the existence of the small set \(T\) implied the existence of \(g\), by contrapositive, such a small set \(T\) could not have existed as well, and therefore, the output of the merger is not concentrated within any small set, meaning that it is close to some high min-entropy distribution.

Lastly, the construction is general enough to also work if there is no uniform distribution among the inputs. In this case, the merger’s output distribution will be close to some distribution having min-entropy roughly as much as the maximum of the min-entropies of the input distributions.